THE LOST LATINX

Why Aren't Haitians Included In Latinx History?

As Latinx Heritage Month once again arrived and consequently passed in October, a question arose: Why were Haitians erased from these celebrations and discussions? In addition to commemorating Dolores Huerta, Cesar Chavez, Berta Caceres, Sonia Cisneros, Cherie Moraga, Cha Cha Jimenez, why weren't Sanite Belair and Toussaint L'Ouverture also included as crucial historical freedom fighters? If Haiti is situated in Latin America, why weren't Latinx students learning about the Haitian Revolution, one of the essential political eras in the Western Hemisphere? Since Haitians speak creole derived from a Latin language — French — where does it fit in question with Latinx political struggles?

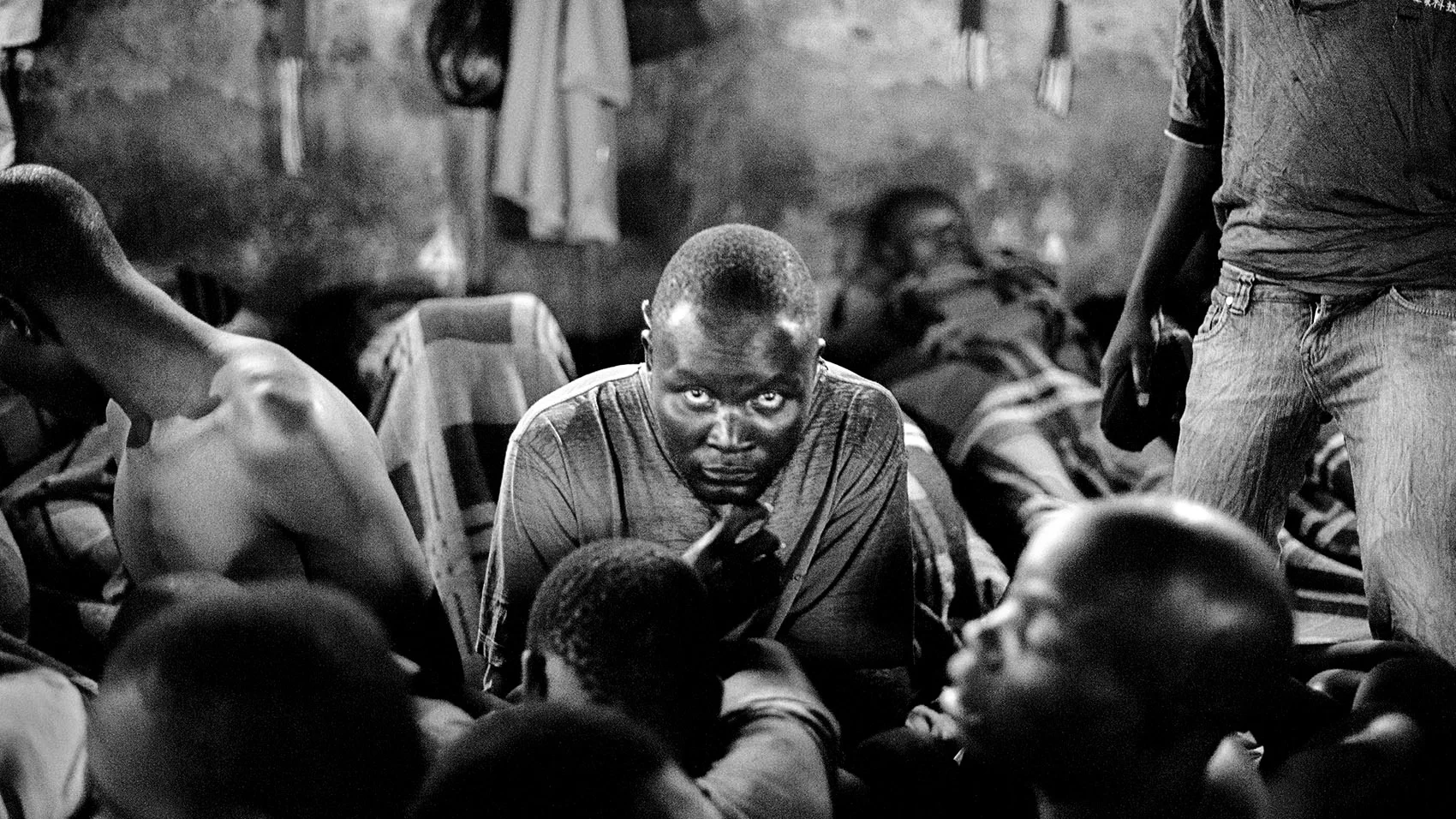

Toussaint L'Ouverture in Bordeaux, France

When Haitians are mentioned in regards to Latinx political, economic, and cultural issues, it's most often about its relationship with the Dominican Republic. As Haiti and the Dominican Republic were once the same country (Hispaniola), a divergent path emerged where once the latter country won its independence from Spain, it actively sought distance from Haiti. While Haitians are notably the first Black nation, the Dominican Republic's national state actively, and occasionally violently, denies Blackness, forging a Latinx identity that instead claims Indian and Spanish heritage.

Haitian culture is unmistakably African — so African that it conflicts with the powerful idea of what it means to be Latinx. As a result of the dismissal of Haiti as a viable part of Latin American history, the term Latinx privileges Spanish colonial influence in the Antilles, Central, and South America. While the Spanish once controlled what is now Haiti under Hispaniola, there is the scant memory of the European empire present, save for the traces of Spanish in Haitian Creole. This anti-Blackness is a profound result of Spain's denigration of African heritage, most noted in the casta system instituted under the Spanish Crown. Despite African Moors ruling the Spanish Iberian Peninsula for nearly eight hundred years, and consequently, transforming Spanish education, food, dance, music, architecture, and politics, the European nation ceases to attribute these achievements to its ancestral African presence.

Haiti's unapologetic dedication to Blackness is often a criterion to other countries of what isn't Latinx. Take Mexico —despite the Central American country's prevalent African and Indigenous lineages, Afro-Mexicans weren't officially recognized as a group in the country until 2015. Afro-Mexicans living in major Mexican cities commonly face police harassment and are even threatened with deportation, under the suspicion that they appear to be Haitian. "The police made me sing the national anthem three times because they thought I was not Mexican. I had to list the governors of five states, too," confessed the Mexican singer El Chogo Bandeno. Bandeno was visiting Mexico's capital when he was stopped by the police, who supposed he was an illegal immigrant. Being Haitian and being Latinx are considered culturally and politically incompatible.

Hugo Marin Gonzalez, a self-identified Boricua, and Afro-Caribbean writer, who renounces the term "Latinx," alludes to the definition of it being centered around colonization. "The ‘Latin' as a race concept was invented by the French in the 19th century, linking themselves to the Americas' territories who spoke Romance languages and used as a justification for their invasion of Mexico," he explains. "To me, being

of Latin origin resonates as of being a colonial trophy for Latin Europe, while ‘Hispanidad' only covers

an insufficient percentage of my cultural heritage." If we are to utilize the term Latinx for revolutionary purposes, how are we to go about including African identity, ancestry, and roots in Haitian culture, disrupting colonialism in the process? How can we expand the definition to include Africans in

the Antilles in the broader inclusion of Latinx identity? Or is it not possible at all due to

colonial indoctrination?

We must examine the space that term Latinx gives people with non-European heritage, and question

why space isn't extended to Haitians. If the crux of understanding Latinx history is based on attempting decolonization, what does it mean when Haitians are exempt from perceptions of resistance in Latin America as people of predominately African descent? We must redefine the idea of what "Latinx" means, in which those who are most marginalized in Latin America are included in radical commemoration.